Understandable information for detainees

A document handed over (or worse, merely shown) to a detainee upon detention may not be comprehensible. This is not only a Polish problem. In other EU countries as well, guidance given to detainees leaves a lot to be desired. Hence, the idea for lawyers and plain-language specialists to join forces to create new sample guidance for detainees.

According to Directive 2012/13/EU on the right to information in criminal proceedings, “Member States shall ensure that suspects or accused persons who are arrested or detained are provided promptly with a written Letter of Rights. … The Letter of Rights shall be drafted in simple and accessible language. … Member States shall ensure that suspects or accused persons receive the Letter of Rights written in a language that they understand.”

Unfortunately, EU member states have not fully implemented these guidelines, or not in the spirit required by the directive. As shown by a comparative law study carried out in 2016 by Fair Trials in cooperation with the Hungarian Helsinki Committee, “Accessible Letters of Rights in Europe,” guidance for detainees is often worded in specialised and inaccessible language, with text cut and pasted from national legal codes. In some countries, persons detained or arrested are even discouraged from exercising their rights, either by officers or by poorly worded guidance. Among the problems identified with the Polish guidance, the survey indicated incomprehensible legal language and a lack of time to read the guidance before an interview (officers often press the detainee to sign a document confirming receipt of the guidance, so they can proceed with the interview).

Therefore, an idea was born to make a grassroots effort to create understandable guidance for detainees, following principles of plain language. To this end, workshops for professionals in criminal procedure were held in 10 member states under the Justice programme financed by the European Commission. The aim was to jointly develop an understandable version of guidance for detainees (based on the current model and the proposal prepared by the organisers). The workshops were organised by the Hungarian Helsinki Committee in agreement with Fair Trials (Belgium), APADOR-CH (Romania) and Antigone (Italy). In Poland, they have been held under the patronage of Wardyński & Partners.

Short, but not to the point

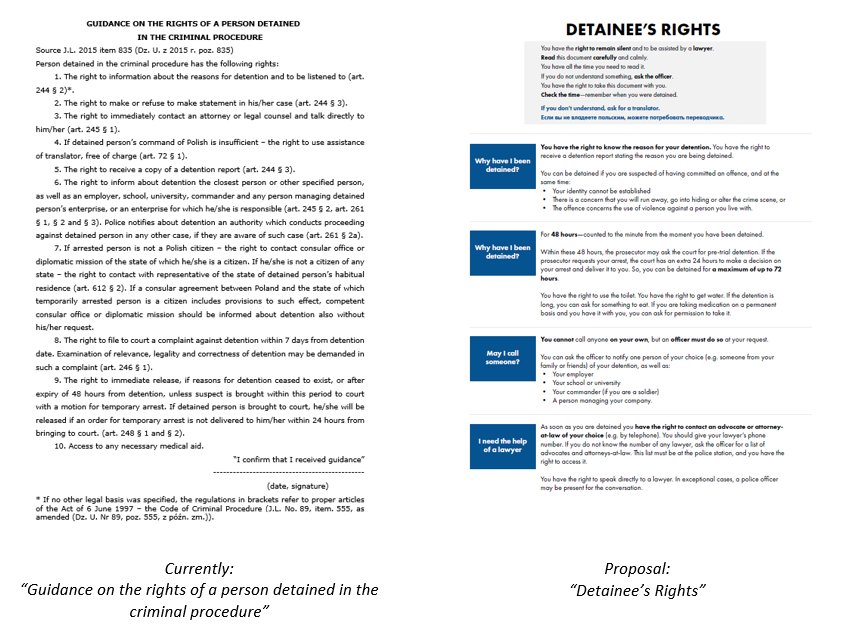

The current guidance in Poland fits on one sheet of A4 paper—but its advantages end there. The guidance is excerpted from sections of the Criminal Procedure Code, with citations to individual articles. The detainee’s rights are generally given in the order they are given in the code. Some of them are described vaguely, others in too much detail. (Moreover, the official English version of the guidance, as issued by the Ministry of Justice, is poorly translated. Below we use quotations from the official English version, warts and all.)

At the beginning, immediately after stating that the detainee has a right to be informed of the reason for detention, the document mentions a “right to be listened to.” This could be misleading, as it might encourage the detainee to talk to officers, against his or her interests and against the right to remain silent. Moreover, the right to remain silent is not clearly stated, but couched in the phrase “The right to make or refuse to make statement in his/her case.”

Some of the wording of the current guidance may be unclear even to lawyers. In the section indicating who may be notified of the detention, what is the difference between a person managing the “detained person’s enterprise” and a person managing “an enterprise for which he/she is responsible”?

Some excerpts also seem to be more relevant to the police than to the detainee (“Police notifies about detention an authority which conducts proceeding against detained person in any other case, if they are aware of such case.”)

One provision states, “If a consular agreement between Poland and the state of which temporarily arrested person is a citizen includes provisions to such effect, competent consular office or diplomatic mission should be informed about detention also without his/her request.” This seems too detailed for what should be a short text. And it is hard to imagine that a detained foreigner would know whether his country has a consular agreement with Poland providing for automatic notification of detention of its citizens. Thus detainees could not know whether they have to explicitly request consular notification (or be sure that the detaining officers know this and are able to answer the question).

So, while the current guidance is indeed condensed to a single page, it does not contain the information the detainee really needs. It is written from the perspective of the institution and not the recipient, not to mention the use of confusing legal language.

Why? For how long? Do I have to agree?

We started working on a proposal for new sample guidance by considering what information the detainee needs, and in what order. According to the principles of plain language, the needs of the recipients (what they would like to know) come first, not the needs of the institution (what we would like to tell them).

So at the beginning is “Why?” and then “How long?” Next: “Can I call someone?” (maybe a lawyer?), “Do I have to answer questions?” and “What do I have to agree to during detention?”

The current guidance does not answer the last question, and to us it seems essential for detainees to know that they may be searched, that medicine, cigarettes and shoelaces may be taken away from him, and that they may be strip-searched or given a breathalyser test. Detention is stressful enough in itself, so it is good to know what to expect. It is also good to know that certain activities are routine and do not necessarily mean that the officers have exceeded their authority.

We listed the rights in the chronological order in which they would probably arise from the detainee’s perspective. Only after practical issues related to the very moment of detention do we answer questions on whether the detainee will receive a document from the detention and whether he can make a complaint. Just above the signature line we warn the detainee, “Do not sign documents you do not understand.” The warning in the Polish form is primarily aimed at people who have little knowledge of Polish, but such a reminder would be useful for anyone.

At the very beginning of the text, we have also added the information for foreigners about the right to a translator, in English and Russian, as even the best-constructed guidance will not work for a non-Polish speaker.

Rights, not guidance

To dot the “i” we changed the title of the document to “Detainee’s Rights.” This was proposed by the workshop participants. Although in English, following the EU directive, the analogous document is called “letter of rights,” the current Polish means “guidance.” That immediately establishes the relationship between the officer and the detainee. This creates an obvious power dynamic, but also suggests a paternalistic relation between “teacher” and “pupil.” This approach could psychologically discourage detainees from exercising their rights.

The stress accompanying detention may also make it difficult for the detainee to process information. Thus we have placed great emphasis on ensuring that the information is not only arranged in a logical order, but is also clearly described, according to the principles of plain language.

The document is in the form of questions and answers. The answers are addressed directly to the recipient (“You have the right,” “You may ask”). The sentences are short and contain many verbs in personal form. We have avoided verbal nouns that are typical of legalese and a barrier to understanding. (The current instructions are worded more impersonally.)

The most important rights are included in a highlighted box just under the title (the right to remain silent, the right to a lawyer, and the right to take as much time as necessary to read the document). We also sought to give the document clear graphics.

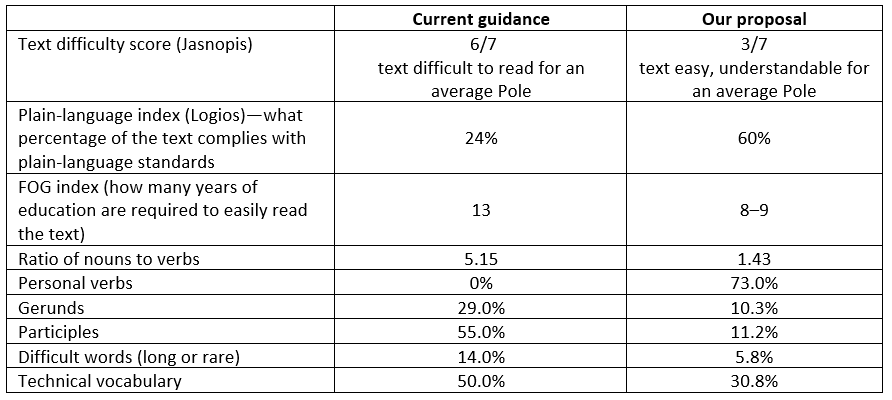

The document has been extended to three pages, but the most important feature of the document (and its true purpose) is not to be crammed onto one page. Rather, it should contain as much information as needed—neither too little nor too much. The comprehensibility score for the text has increased significantly (as confirmed for the Polish version by two widely available tools for assessing comprehensibility, Jasnopis and Logios). The existing guidance is written at an undergraduate’s level. Our proposal is understandable to a primary school graduate.

A different look

The proposal in this form has been submitted to Fair Trials, and from where it is to be forwarded to the European Commission. But we would really like this document to take on a life of its own—if not as official guidance for detainees, then as material distributed online. Thus we encourage readers to download and share it.

The aim is not only to satisfy the EU requirements on the right to information in criminal proceedings. More comprehensible guidance also means less work for lawyers, prosecutors, judges and police officers, but most importantly, helps individuals actually enforce their rights.

The detainee’s rights proposal was created in the course of workshops attended by judges, scholars, advocates, attorneys-at-law and trainees. We thank the participants for their commitment and valuable comments. We encourage readers to share the document we have developed jointly.

Justyna Zandberg-Malec, plain-language specialist, Wardyński & Partners

Artur Pietryka, adwokat, Maria Kozłowska, adwokat, Business Crime practice, Wardyński & Partners