The electricity market: Prospects for renewable producers after winning an auction

The situation on the energy market has never been so dynamic. Many claim that high energy prices will not allow economic growth to be sustained, and will lower consumers’ standard of living. It would seem that at least generators of electricity from renewable energy sources are happy about the higher energy prices on the market, as they can sell power for more while keeping production costs relatively low. But when these producers participate in the RES auction support system, their situation becomes more complicated than it might seem at first glance.

The conflict in Ukraine has destabilised the commodity and energy markets. No one questions anymore the necessity of energy price increases for end users, which from 2023 could reach up to 50% in the regulated market. Additionally, the president of Poland’s Energy Regulatory Office is receiving requests to increase energy tariffs during the course of the year. Until now, such a situation had occurred sporadically, but now there are many more such requests.

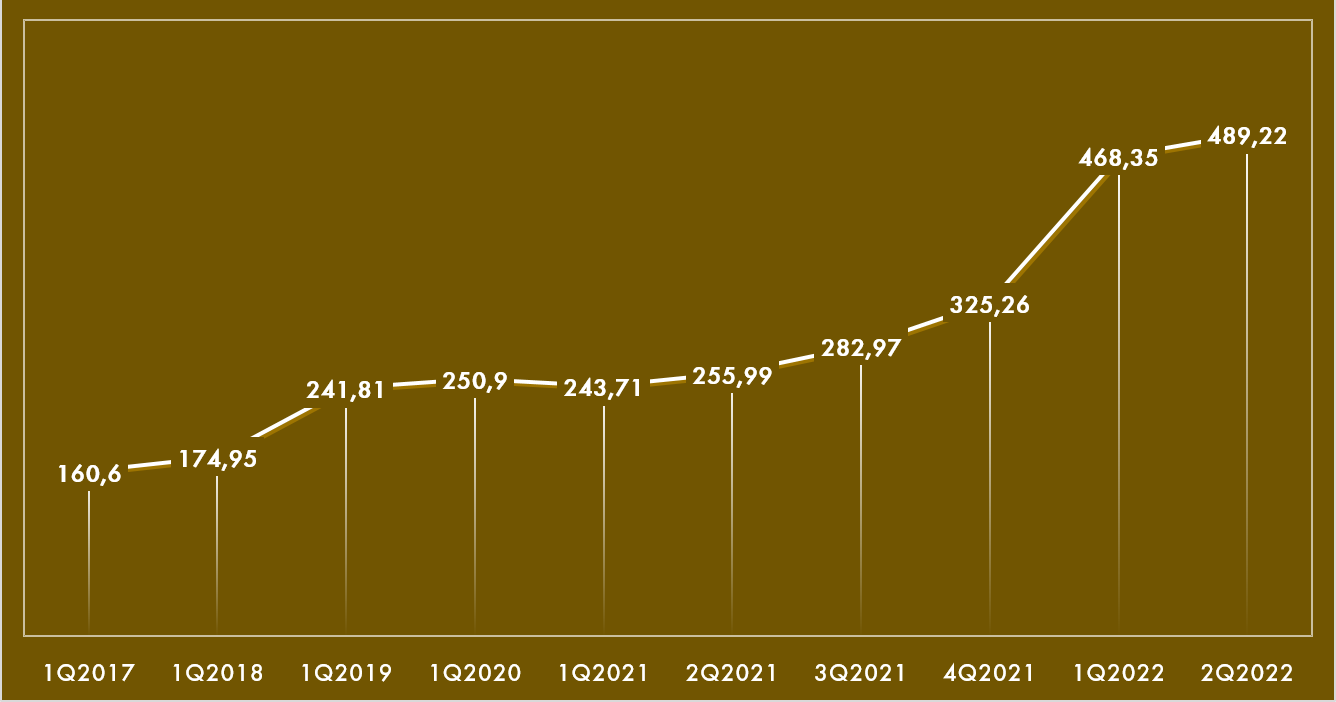

Electricity price on the exchange and in auctions

In the 1st quarter of 2022, the average price of electricity in the competitive market exceeded PLN 468/MWh. But as recently as June 2022, the energy exchange price oscillated around PLN 885/MWh (by comparison, in June 2021 it was about PLN 355/MWh), to reach almost PLN 1,126/MWh in July—a nearly threefold increase in one year. It is tempting to say that few were surprised that the July 2022 average exceeded PLN 1,000 per MWh.

AVERAGE SALE PRICE OF ELECTRICITY ON THE COMPETITIVE MARKET (PLN/MWh)

Source: Energy Regulatory Office

Meanwhile, the maximum possible price that a producer can offer at an auction (the reference price) was only PLN 250/MWh in 2020 for installations above 1 MW of installed capacity for onshore wind, and PLN 340/MWh for solar energy, with a downward trend due to falling operating costs and increased generating efficiency.

This means that producers who submitted a winning bid and have started (or will start) producing under the auction support system would, at the start of their operations, already be able to sell electricity for a much higher price than they indicated when submitting their bid in the RES auction.

The mechanism of contracts for difference is based on a system of subsidies or refund of the difference depending on the price obtained. For producers, this means that:

- When the price obtained on the market is lower than the price set in the contract, the producer receives a subsidy

- When the price obtained on the market is higher than the designated price, the producer is obliged to turn over the excess.

Thus, at current electricity prices, the producer not only receives no subsidiary, but still has to return the difference. This is because RES producers participating in the support system report to the settlement administrator the data indicating the achievement of a positive balance, i.e. the aforementioned revenue surplus obtained by selling energy on the market at a price higher than the price determined by the contract for difference concluded due to winning the RES auction. Under the recently changed rules (and contrary to the original assumptions of the auction support system), producers will be forced to return the value of the balance if they are further in the black at the end of the three-year settlement period (or the support period in general) with revenue generated from energy sales. Unsurprisingly, RES energy producers in Poland have begun to look for ways to reduce the need to turn over revenues generated thanks to the current high market prices for power.

The RES auctions allow producers the comfort of knowing that an installation will generate revenue at the level guaranteed by the state when winning the auction, something that banks value in particular. However, a producer bidding in an auction does not have the obligation to report to the system the entire volume of energy planned to be produced during the support period. Additionally, once the producer is a participant in the support system, it does not have to sell within the system the entire volume declared in the auction winning bid—the president of the Energy Regulatory Office may impose a fine only for failure to sell at least 85% of the energy declared within the system. This further allows for reduction of the amount of energy reported under the support system in relation to the energy actually produced in a given period, thereby reducing the value of the generated positive balance.

The relative flexibility of the rules as to the volume to be sold under this system was dictated by the volatility of RES, and thus responded to the fluctuations in energy production occurring in the case of RES. However, it turns out that in the current situation, this flexibility can be used in ways that were probably not foreseen by the architects of the support system. What is more, given the surge in market prices for energy and the delay in the potential imposition of penalties, it may be worthwhile for producers to declare understated volumes (or even a “zero balance”) and subsequently pay a fine. The intention behind this approach would be not to generate a positive balance that would be refundable. The rules for the support system do not seem to prohibit such behaviour. What is more, this procedure also seems to be accepted by banks that have provided financing for construction of installations based on revenue projections calculated on the basis of values declared by producers in bids submitted under the auction system.

Calculation of the fine

Imposition of a fine by the president of the Energy Regulatory Office will occur after an unspecified period, further prolonged by the lengthiness of the administrative proceedings, a potentially large number of similar proceedings, as well as the regulator’s limited staff resources. The principal problem may consist in estimating the amount of the fine that, presumably, will sooner or later be imposed by the regulator, as it is not clear which specific energy price should be used to calculate the penalty. Several different numbers can be inserted into the formula for calculating the penalty:

- The bid price

- The bid price after indexation in a given year

- The bid price after indexation at the end of the settlement period

- The price as of issuance of the penalty decision (so in the year following the end of the settlement period, or even later).

Obviously, the lower the value in the formula for the fine, the greater the temptation for energy producers not to report energy volumes in their monthly declarations under the auction system, and thus benefit from all the revenue generated from the sale of electricity. Nonetheless, at some indefinite point in the future, a fine will have to be deducted from these profits for failing to meet 85% of the volume from the winning auction bid within the system.

Thus, in practice, an RES producer can “opt out” of participating in the auction system until it is profitable to do so, bearing in mind the entire 15-year support period. Opting out in this case would mean failure to fulfil the commitment to provide a minimum of 85% of the volume of electricity specified in the auction bid in each (or all) of the three-year settlement periods. In making this decision, the producer can be guided by the direct relationship between the electricity prices on the market and the value of the fine that would be imposed by the regulator according to the statutory conversion factor.

And outside the auction system…

It should thus not be surprising that producers of electricity are increasingly looking to sell energy outside the auction system, at the market price, without returning a positive balance. Therefore, corporate power purchase agreements (cPPAs) are gaining in importance, not only, as before, as an alternative to the support system in general, but also potentially as contracts operating alongside the support system, due to the juggling by the producers of the amount of energy reported under the system. A cPPA involves a direct sale of electricity from a generating source to the end user (or, depending on the variant, also with an entity providing balancing of the source’s generation shortfall). Meanwhile, there are also specific conditions associated with the functioning of such agreements determining their practical feasibility (balancing, price hedging, contract period, specifics of the recipient’s energy consumption, etc).

However, it seems that economies of scale and greater revenue (notwithstanding the fine for abandoning the auction system) may compensate for the additional costs involved with it. Therefore, the next steps taken by power producers will probably be dictated by an economic calculation set forth in a spreadsheet.

Marek Dolatowski, attorney-at-law, Łukasz Bondaruk, adwokat, Energy practice, Wardyński & Partners