The Artificial Intelligence Act and new obligations for developers and users of AI

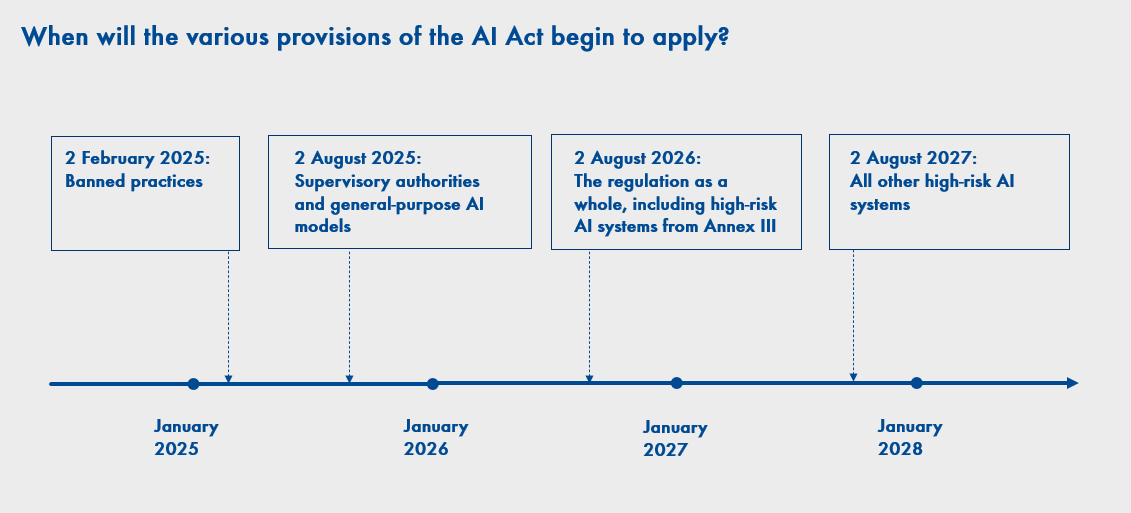

The Artificial Intelligence Act (Regulation (EU) 2024/1689) entered into force on 2 August 2024. In most respects the regulation will apply from 2 August 2026.

The AI Act also includes grace periods enabling entities covered by the regulation to adapt to their new obligations.

- 2 February 2025: provisions on banned AI practices will start to apply

- 2 August 2025: provisions on supervisory authorities and general-purpose AI models will start to apply

- 2 August 2027: provisions on all high-risk AI systems other than those listed in Annex III to the regulation will start to apply.

What does the AI Act regulate?

Contrary to popular belief, the AI Act does not regulate all legal aspects of the use of artificial intelligence in the European Union. Primarily, the act focuses on systems deemed to pose a high risk to the functioning of society (e.g. AI systems applied in education or employment, or using biometrics) and general-purpose AI models and systems (such as ChatGPT).

The AI Act sets forth:

Which AI practices are banned, and which AI systems can be classified as high-risk?

European lawmakers perceive many beneficial applications of AI that can improve quality of life, but also many risks to health, safety, and fundamental rights that can result from the application of AI systems. Under the AI Act, certain practices using AI systems are banned because they are contrary to EU values.

The list of prohibited practices includes practices involving placing on the market, putting into service or using an AI system that:

- Deploys subliminal techniques beyond a person’s consciousness, or purposefully manipulative or deceptive techniques

- Exploits vulnerabilities of a natural person or a specific group of persons due to their age, disability, or specific social or economic situation, with the objective or effect of materially distorting the behaviour of that person or a person belonging to that group in a manner that causes or is reasonably likely to cause that person or another person significant harm

- Is used to carry out risk assessments of natural persons in order to assess or predict the risk of a natural person committing a criminal offence, based solely on the profiling of a natural person or on assessing their personality traits and characteristics (but this prohibition does not apply to AI systems used to support the human assessment of the involvement of a person in a criminal activity, which is already based on objective and verifiable facts)

- Creates or expands facial recognition databases through the untargeted scraping of facial images from the internet or CCTV footage

- Is used to infer the emotions of a natural person in the workplace or at an educational institution (unless the AI system is intended for medical or safety purposes)

- Based on biometric data, categorises natural persons individually to deduce or infer their race, political opinions, trade union membership, religious or philosophical beliefs, sex life or sexual orientation (this ban is not absolute).

The full list of banned practices is found in Art. 5 of the AI Act.

Failure to comply with these bans is subject to an administrative fine of up to EUR 35 million or 7% of the undertaking’s total worldwide turnover in the previous financial year.

High-risk AI systems are systems regarded by EU lawmakers as likely to have a detrimental impact on health, safety, or rights protected under the Charter of Fundamental Rights, and whose use should therefore be subject to heightened supervision. These systems are defined in Art. 6 of the AI Act and are divided into two categories. The first category, in Art. 6(1), indicates the prerequisites for a given AI system to be considered high-risk. The second category, in Art. 6(2), cross-references Annex III to the AI Act, which lists types of systems considered high-risk. These include systems:

- Using biometrics

- Designed to make decisions about access or admission to educational institutions, recruitment, or advancement at work

- Designed to assess natural persons’ eligibility for essential public benefits and services, their creditworthiness, or insurance prices.

Entities that do not comply with the obligations set out in the AI Act regarding high-risk systems may be subject to an administrative fine of up to EUR 15,000,000 or 3% of their total annual worldwide turnover.

Obligations stemming from the AI Act

The AI Act imposes different obligations on entities involved in creation and use of AI systems depending on their role in the supply chain, as well as their method of using AI. Therefore, such entities need to carefully identify their role in each situation where they use AI in their operations. In this respect, the AI Act distinguishes between “providers,” “importers,” “distributors” and “deployers.” While the definitions of “importer” and “distributor” are fairly intuitive, classifying an entity as a “provider” or “deployer” can be disputable.

An AI provider is any entity that develops an AI system or a general-purpose AI model or that has an AI system or a general-purpose AI model developed and places it on the market or puts the AI system into service under its own name or trademark.

Meanwhile, any user of an AI system is regarded as a deployer within the meaning of the AI Act, except where the AI system is used in the course of a personal non-professional activity. Therefore, if someone generates images using AI systems for private purposes, they do not need to be concerned about the obligations imposed on deployers of AI systems under the AI Act.

Additionally, if someone repurposes an AI system that was put on the market not as a high-risk AI system, in such a way that the AI system becomes a high-risk AI system, then they become a high-risk system provider. A change might consist for example of an add-on allowing the AI system to recognise human emotions, when the AI system was not supplied for that purpose.

The obligations under the AI Act are quite different depending on what functionality is attributed to tools using AI systems, whether the AI system supplied by the provider is modified, or whether such changes alter the purpose of the system.

Given the scope of this article, we do not cover here the obligations for general-purpose AI models.

Deployer’s obligations

Users of a high-risk AI system must ensure that the system is used in accordance with the accompanying operating instructions, supervised by a human, and that the inputs (to the extent that the user has control over them) are adequate and sufficiently representative of the purpose of the AI system. Deployers also have an obligation to monitor and report irregularities to high-risk AI system providers and supervisory authorities, and to adequately safeguard data in records and inform employees and other persons of the use of high-risk AI systems in relation to them (Art. 26 (7) and (11)).

And in the case of systems for recognising emotions or biometric categorisation, deployers must inform the natural persons to whom these systems are applied accordingly.

In addition, if a deployer uses an AI system to:

- Generate or manipulate images, audio or video content constituting a “deep fake,” or

- Generate or manipulate a text published for the purpose of informing the public on matters of public interest,

the deployer must disclose that the content has been artificially generated or manipulated.

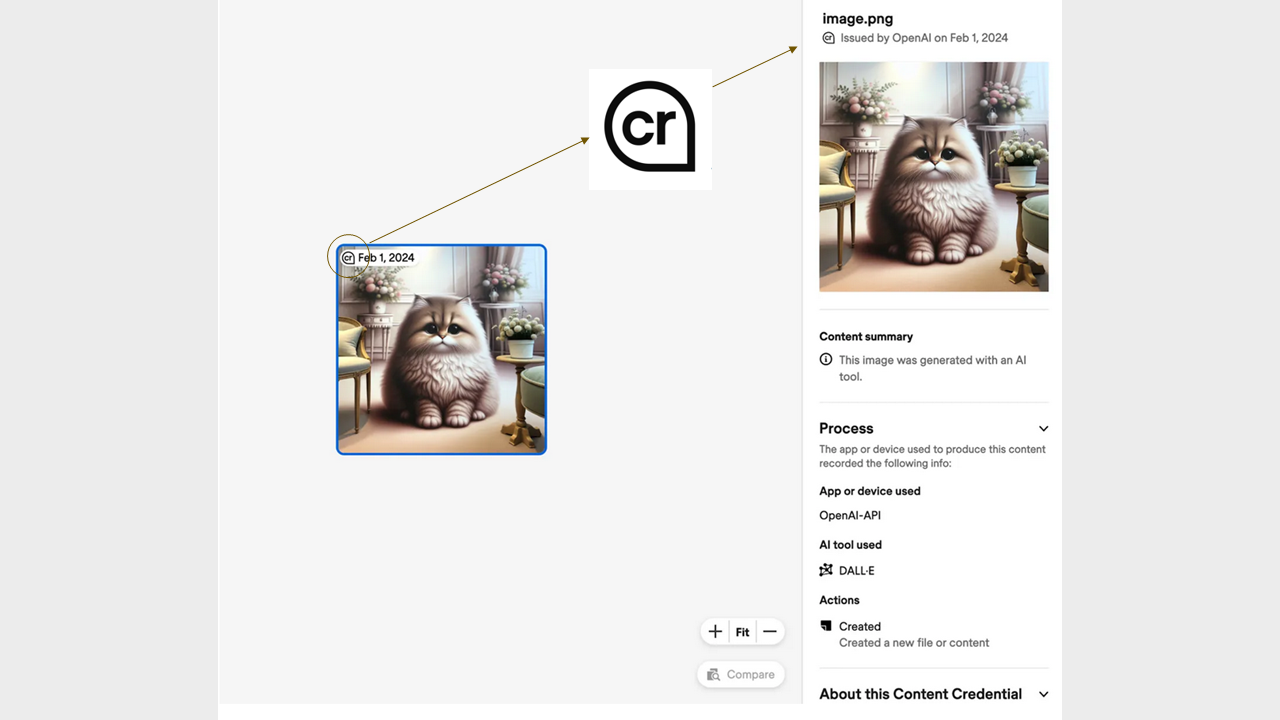

The AI Act does not specify how deployers should comply with this obligation. The designations currently used on the market are not uniform. Some examples:

- “Who owns copyright to AI works?” prompt, ChatGPT, 13 Feb. version, OpenAI, 16 February 2023, chat.openai.com

- “Pointillist painting of a sheep in a sunny field of blue flowers” prompt, DALL-E, version 2, OpenAI, 8 Mar. 2023, labs.openai.com

- “AI-generated”

- “Generated with an AI tool”

- “AI-manipulated.”

Provider’s obligations

The obligations of an AI system provider depend on whether or not it is a high-risk system.

Providers of high-risk systems must:

- Implement a quality management system

- Prepare relevant technical documentation

- Provide human oversight of the AI system

- Monitor the AI system after placing it on the market and report serious incidents to the supervisory authorities

- Complete formalities for registration and compliance with the AI Act

- Maintain records of incidents

- Cooperate with the competent authorities

- Register themselves and their system in a special EU database.

For AI systems:

- Designed to interact directly with natural persons, or

- Generating content in the form of synthetic sounds, images, video or text,

deployers have an additional obligation to:

- Inform natural persons who interact directly with the AI system that they are interacting with an AI system

- Ensure that the results of the AI system are designated in a machine-readable format and will be detectable as artificially generated or manipulated.

This means that all systems used to generate content using AI from the starting date of application of the AI Act, i.e. from 2 August 2026, must have the functionality to designate that the content was generated using AI. Thus there is still time to prepare for application of the AI Act and rethink the strategy for use of tools based on AI systems.

However, the AI Act does not specify the method for designating results of using AI systems. The market practice shows that different providers of AI-assisted content creation solutions use different designations. In this context, it is worth noting the Coalition for Content Provenance and Authenticity (C2PA). Founded in 2019, the coalition aims to create technical standards to certify the source and origin of content. Within the coalition, it has been proposed to use the CR icon to indicate the source of a particular graphic.

“CR” is an abbreviation of “Content CRedentials.” The aim is that when the cursor hovers over the CR icon, information should open up about such items as the AI tool used to prepare the graphic and other details about its production. Irrespective of the CR icon, many providers also use invisible watermarks in the file’s metadata, in the format recommended by C2PA or other format indicating that the file was generated using AI.

Source: https://www.theverge.com/2024/2/6/24063954/ai-watermarks-dalle3-openai-content-credentials

The method of designating the content and informing people that they are entering into direct interaction with AI systems is likely to be detailed in future guidelines.

The European Commission is already promoting the AI Pact, under which AI providers and deployers will voluntarily implement the AI Act before the indicated deadlines. The AI Pact also encourages the exchange of best practices and provides practical information on the process of implementing the AI Act between affiliated entities.

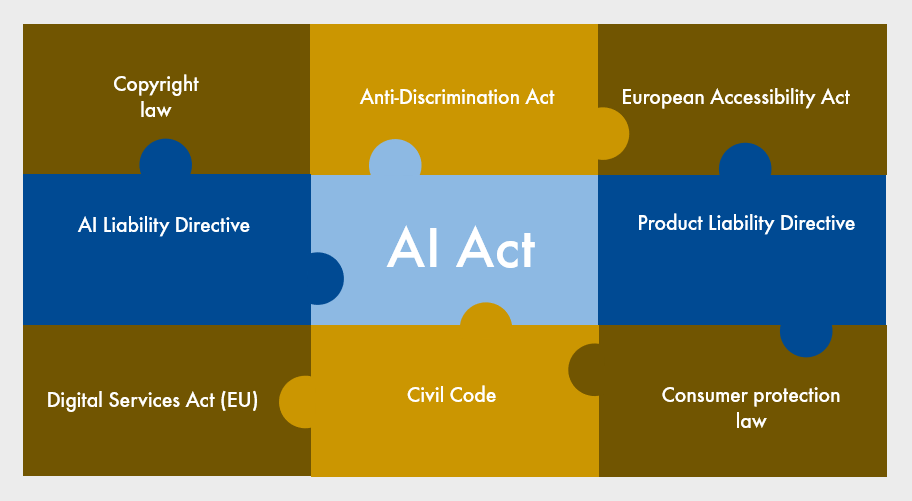

Is this all the regulations governing AI?

No—many issues concerning artificial intelligence are regulated by industry-specific laws in Poland or across the EU. Some of these laws that must be taken into account include:

Ewa Nagy, attorney-at-law, Intellectual Property practice, Wardyński & Partners