Image crises and the influence of culture and history on video games

There is no single recipe for success in the video game market, but some causes of problems at the distribution stage are clear. In this article, we take a cultural and historical look at the content of games. These aspects may force the producer to introduce changes in such areas as quests or a character’s appearance or “skin.” It is not always enough to meticulously analyse the game content for intellectual property issues. Sometimes it will be better to abandon some content ideas or even create several versions of a game, adapting the content to the market where the game is to be distributed.

Protected symbolism

Some international or national symbols are subject to special protection.

The sign of the Red Cross, familiar to all, is a symbol of humanitarian aid, protected by international law and the national law of many countries. Contrary to general belief, it is not part of the public domain; it cannot be used by anyone in any way. The rules for use of the Red Cross symbol are strictly defined in the Geneva Conventions, and improper use not only violates the law but, above all, distorts the meaning of the sign, deepening the perception that it can be used freely, which detracts from its value.

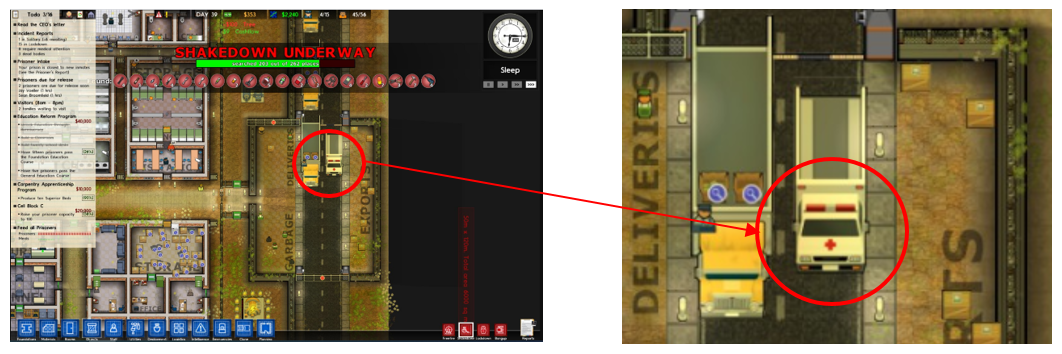

This sign has appeared in many games. In the well-known case of Prison Architect, the sign was placed on the hood of an ambulance. The British Red Cross successfully requested that the producer remove the sign from the game.

Certain symbols may be protected under national law, for example national emblems or military symbols. Thus emblems of the branches of the Polish Armed Forces may only be used by military units. However, the law allows insignia modelled on those of the Polish Armed Forces to be used elsewhere with the consent of the Minister of National Defence (Art. 2(2) of the Act on the Emblems of the Armed Forces of the Republic of Poland of 19 February 1993). In practice, this means that the creators of a game with a historical context, in which it is planned to use historical insignia similar to those of the Armed Forces, such as those indicated below, must take into account the need to obtain permission for their use.Source: PC Gamer

| Checkerboard on a Polish Air Force plane |

|

| Flag of war on a Polish Navy vessel |

|

| Eagle of the Land Forces on a soldier’s uniform |

|

Elements banned from games

Nowadays, when access to all kinds of content is basically very easy, many countries place a special emphasis on ensuring that messages targeted to children and young people are not harmful to them. The PEGI age-rating system is used in Europe (except for Germany). An age rating means that the game is suitable for a player of a certain age. Other systems operate for example in the United States or China. States adopt laws and implement policies to prevent access by this audience to, among other things, violent or sexual content.

Let’s take China as an example. Games that show violence, such as torture, corpses, skeletons, human entrails or blood, could not be distributed there. In an effort to bring the game in line with existing bans, some producers changed the colour of blood from red to green or some other colour. These actions were quickly curtailed, as the rules for refusing permission to distribute a game in the Chinese market were clarified in 2019 to explicitly state that games must not contain any corpses, skeletons, zombies, vampires, or blood of any colour, and a character who is killed must quickly disappear. The word “kill” cannot appear in the game. (This discussion is based on “Content Restrictions and Requirements for Publishing Games in China” (2020), “China’s new rules on video games: No blood, dead bodies, or mahjong,” “The Chinese are banning the word ‘kill’ from their games and getting rid of blood! The clever PUBG developers are changing its color... to green,” and The Future Is Bloodless! China Bans Blood in Video Games.”)

One of the many examples of games amended due to Chinese regulations is World of Warcraft. Among other things, the version distributed in the Chinese market does not depict entrails or skeletons.

| World of Warcraft: basic version | World of Warcraft: Chinese version |

Source: YouTube

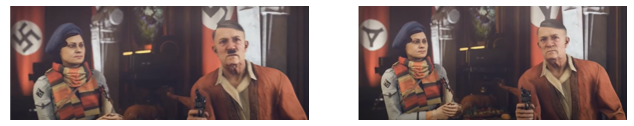

However, violence is not the only taboo in games. In many countries, it is forbidden to promote Nazi ideology, and state authorities keep a close eye on games to ensure they do not contain any content related to this subject. This was fought particularly strongly by Germany, which did not allow the distribution of games showing, for example, swastikas or Adolf Hitler’s face. It is for this reason that Wolfenstein II replaced swastikas with triangles, and Hitler with a dictator named Herr Heile without the trademark moustache.

| Wolfenstein II: basic version | Wolfenstein II: German version |

Source: YouTube

In 2019, the German self-policing organisation for software USK (Unterhaltungssoftware Selbstkontrolle), which rates software for the safety of children and young people, decided that the blanket ban on Nazi symbols in games, which had been in place for years, would be replaced by an individual examination of each game. This does not mean that a game with such symbols will definitely be allowed on this market, but at least there is now a chance that this will happen.

But sometimes a distribution ban can turn into something much bigger than just a ban on selling a game in a particular country. We return to China for the high-profile case of Battlefield 4 (e.g. “China Issues Blanket Battlefield 4 Ban”). Not only was distribution of the game banned there, but also the use of any materials related to the game, including the demo, and the game’s name in Chinese (ZhanDi4) was listed as a censored word on China’s largest social network, Weibo. What caused such a reaction from China? The game was considered detrimental to the country’s image and a cultural threat, as the plot involves a coup d’état in China, and the player, a member of an American special unit, has to fight the Chinese army, among others, as a result of which many dead Chinese soldiers appear in the game.

Without a doubt, at least some countries are particularly vulnerable if a game shows them in a bad light or the action of the game involves an armed attack on that country. Battlefield 3 was banned in Iran because Teheran was one of the cities invaded by US troops in the game. The services inspected shops selling the game in Iran, and Iranian youth collected signatures for a petition against the game. (In fact, the developer, EA, had no distributors there, so legal copies of the game were not for sale in that territory at all.)

Cultural appropriation in games

Avoiding state symbols or promotion of certain ideas is one aspect of making sure a game has good PR. Developers should also be sensitive to the use of religious elements or those drawn from cultural traditions.

For example, the release of LittleBigPlanet was halted after intervention by a players who claimed to hear verses from the Koran in the game’s soundtrack. He posted a comment on a forum of the publisher, Sony, indicating that linking music to scriptural verses is offensive to the Muslim community, and expressed hope that the music would be removed from the game. Sony took the claim very seriously, which resulted in removal of the vocal track, publication of an apology by the developer, Media Molecule, and delay of the game’s worldwide release.

What else might someone find offensive? Some games contain authentic symbols and signs specific to certain groups. H1Z1 used a character who wore a green lavalava (Polynesian kilt), some Polynesian tattoos, and a tā moko mask with a pūkana expression that some believed mocked Maori culture. Eventually, after a wave of criticism swept the gaming community, it was decided to remove the controversial elements from the game.

Source: TVNZ 1 News

References to Maori culture and tradition are also present in Far Cry 3, where the main character, Jason Brody, a 25-year-old American, finds himself on a Pacific island inhabited by people who resemble the Maori because of their characteristic tattoos. At the beginning of the game, Jason receives a tattoo on his left forearm, which is gradually enhanced as the game progresses. However, the tattoo formed on Jason’s body is not specific to the Maori, but to the people of Samoa. The game has been accused of racism and implying that people of the South Pacific need a “white saviour.” The game publisher did not admit to cultural appropriation, but issued statements claiming that the goal was to create a parody of the shooter game genre (see Tova Svensson, “Cultural Appropriation in Games: A Comparative Study Between Far Cry 3 (2012), Overwatch (2016) and Horizon Zero Dawn (2017)”).

To avoid such mishaps, some game developers and publishers hire outside consultants when producing games. The publisher of the expansion pack Civilization VI: Gathering Storm consulted with the Māori New Zealand Arts & Crafts Institute during development of the game to ensure that it presented the culture accurately and respectfully. The developers of Assassin’s Creed III decided to take a similar step by consulting the Mohawk people.

Missteps

When creating a game, the developers must not forget about historical aspects and social conditions. It is also easy to slip up in this area.

“Little Boy” and “Fat Man” were the code names of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. Not surprisingly, the quest to blow up Megaton City with a bomb called “Fat Man” caused Fallout 3 to be suspended in Japan. The game was only launched after that element was removed.

Hearts of Iron suffered a mishap in China. The game maps showed Taiwan under the control of Japan, and Tibet, Xinjiang and Manchuria as independent states, which was seen as a distortion of history and detrimental to China’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. As a result, unsurprisingly, the game was banned from distribution in Chinese territory.

On the Polish market, the premiere of Medium was accompanied by a scandal. The game included eight whistles, alluding to a slogan chanted during social protests in Poland, and the inscription “Beast from Wadowice,” a reference to a film about John Paul II where the late pope is presented as a criminal. Upon learning of this content, the game producer issued a statement denying that its inclusion in the game was intentional, and removed the controversial elements of the game.

Another Polish game whose distribution sparked a scandal is entitled Operation Glemp. This game, with a fairly uncomplicated plot, has stirred a number of controversies due to its anticlerical and mocking storyline. The game shows Poland ruled by a mafia led by the Council of Bishops and headed by a leader nicknamed Glemp. (The late Catholic Primate of Poland was Józef Cardinal Glemp.) The task of the game’s main character was to break out of a prison in the basement of the bishop’s palace, murdering several famous people and blowing up the palace. The game only became controversial a few years after its release due to the media coverage of the issue. Eventually, it was removed from Polish servers, but after some time it was available for download from American servers.Source: Polygamia.pl

Consequences

The lack of knowledge or sensitivity to social, cultural or historical issues can lead to an image crisis for a video game or even delay or stop distribution of the game. But what about the legal implications? Even if certain behaviours or use of certain symbols or references is acceptable in the game developer’s country, that does not mean that it is also acceptable in the country where the game is to be distributed. It is important to keep this in mind, especially since games are in most cases created with the intention of worldwide distribution.

The most serious consequence of breaking the law would be a ban on distribution of the game in a given territory. If a game contains banned content, it may not be allowed to be sold in a given country (as in the examples regarding distribution of games in China or Germany). But that is not all.

Breaking the law can expose game developers and publishers to legal proceedings, including criminal proceedings or fines. For example, the use of state symbols without consent of the relevant authorities, or the use of proprietary marks of international organisations, may constitute an offence. History shows cases where criminal prosecutions have been initiated as a result of a game storyline. The case of the creator of the AntyKomor portal is well known in Poland. In connection with publication of a game enabling players to shoot at Bronisław Komorowski, among others, the developer was accused of insulting the then-President of Poland. However, the case was dismissed on appeal (Łódź Court of Appeal judgment of 17 January 2013, case no. II AKa 273/12). And it seems that it can never be ruled out that the content of any game touching on the religious sphere might prove controversial enough that some person will complain to the prosecutor’s office that the game offends his or her religious sensibilities.

Criminal proceedings are not everything. Lack of moderation or an attempt to smuggle controversial content into a game may end up, for example, with a lawsuit alleging infringement of personal rights, if the content allegedly offends religious sentiments or social or ethnic groups. And the use of symbols in a manner casting Poland in a bad light, blatantly contradicting history, or presenting other defamatory content, could expose one to a lawsuit for protection of the good name of the Republic of Poland or the Polish nation.

Summary

When creating a game, it’s not enough to come up with a catchy idea and pursue technical implementation and marketing. The developer and publisher should also consider whether the game could expose them to legal liability or an image crisis. On one hand, this requires familiarity with national and international law, or at least a sense of when to seek advice in this area. On the other hand, basic historical and cultural knowledge is essential if the game is not only to be attractive and engaging, but also fit into the legal and cultural framework of the place where it is to be distributed.

Ewa Nagy, attorney-at-law, Paulina Mleczak, attorney-at-law, Intellectual Property practice, Wardyński & Partners