How to protect against game clones?

In our series we have addressed the issue of protecting a video game against cloning in the context of lack of legal protection for an idea for a game. In this article, we will take a broader look at this problem.

Cloning in the game development industry means creating video games similar to games that have already gained popularity in the market. But clones are not exact copies of their originals. Therefore, it is hard to accuse them of plagiarism, which would be obvious infringement of the copyright to the original game. Clones deliberately avoid imitating the original 1:1, but take over selected elements of the original. Relatively uncomplicated games are the most cloned, but sometimes more complex games are also attacked by clones (see M. Balicki, “The right to register an industrial design as a tool to protect video games from cloning,” in E. Traple (ed.), Protecting the computer game, and the example discussed there of the dispute between the developers of Deer Hunter 2014 and Kill Shot).

A clone, a fangame, or a game in the genre or type of another game?

Typical clones are almost a copy of an existing game, with a few additions coming from the cloners. The developers of these kinds of imitative games perceive creating a clone as a relatively safe and low-risk investment. Knowing that the original is popular, they hope that a very similar game will also become popular so they can earn money. The spread of this phenomenon is fostered by the frequent cloning of games created by indie developers, who usually do not have significant financial resources to pursue their rights and claims in court. This allows cloners to operate with a sense of impunity.

Another category of clones is fangames: games created by fans, for example as a continuation of the plot of a game or an alternative version. Such ventures are rarely created out of a desire to gain financial benefits. More often, they are a sort of a tribute to the creators of the original game. Some game developers even allow fans to create game modifications. For example, the creators of Unreal Tournament 2004 decided to take such a step. Moreover, Epic Games, publisher of Unreal Tournament, used to organise a contest offering financial and material prizes to creators of modifications to their games. To place this phenomenon in the framework of copyright law, we might consider fangames as works derivative of the original works that are the basis for fans to create modifications and continuations.

Also, some game producers release the source code of the game or make it available for use under licence under certain conditions, e.g. for non-commercial use only.

But for some clones, only unprotected elements of the original game, such as the game idea itself, are copied. For example, there are a number of games alluding to Grand Theft Auto, known as “GTA clones.”

Cloning is on the rise

With the advent of games designed for mobile devices, game sales have shifted to app distribution platforms, making it much easier for game clones to reach potential users.

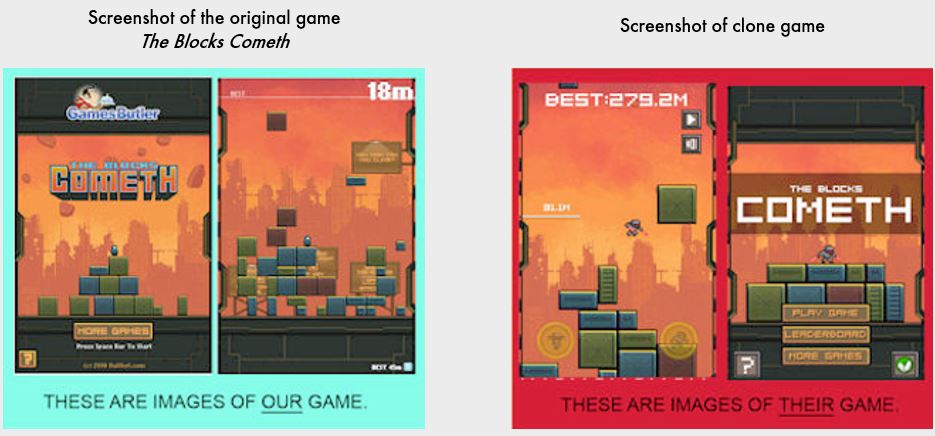

With this new way of distributing games, a bizarre situation happened to the creators of The Blocks Cometh. As soon as they shared the news that they were going to release the game for mobile devices, an unrelated entity launched a game under the same title, with the same concept and almost identical graphics, on the App Store. Before the developers and Apple had time to react, the clone made it to the list of top 100 best-selling apps.

source: arstechnica.com

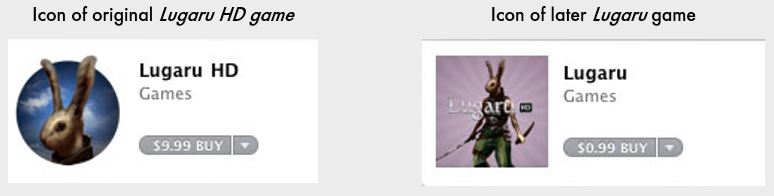

An analogous situation occurred with the game Lugaru HD. When its developers released the game source code under a GPL licence, iCloner launched its clone on the App Store, calling it Lugaru (without the HD in the title), selling for 99 cents, while the original game cost USD 9.99 in the same store. The game icon in the App Store, while not identical, alluded to the original game icon.

source: engadget.com

How to fight cloning?

Evidently, cloning is not a marginal phenomenon. But how can developers effectively protect against it? Unfortunately, the answer is not obvious.

In the first place, protection against cloning is usually sought under copyright law, which does not require any application or registration; protection is enjoyed by operation of law. However, doubts may arise as to what elements of the game are subject to copyright protection, and to what extent. As we have written, the very idea of the game is not protected. So, if the creator of a clone uses the idea of a popular game, but uses different graphics and music, and changes some of its elements, it will most likely be regarded as merely “inspired” by the original work. If the creator took the idea for the game and certain scenes from the original, and added other original elements, such a game should be classified as a derivative work or a work with borrowings. Clones will rarely involve plagiarism of the original game in its pure form, because usually in game clones, in addition to the acquired elements there are also elements coming from the creators of the clones, displaying a certain level of individuality and originality.

An inspired work

An inspired work is a completely independent work with discernible elements modelled on (or inspired by) another work. In the case of inspired works, however, the creative elements of other works are not taken over in part or in whole. In the case of video games, the same game idea and logic (an unprotectable element) may be used, but with completely different graphics, music, characters, storyline, etc. If it is considered an inspired work, there is no copyright infringement and the original author will have no right to claim copyright protection.

Derivative work and work with borrowings

If, on the other hand, a creative element of the original game has been taken over, e.g. the appearance of a particular character, the appearance of the game board or the graphic design of particular scenes, then the creators of the original game can seek an injunction against infringement of their copyright, removal of the effects of the infringement, and monetary relief.

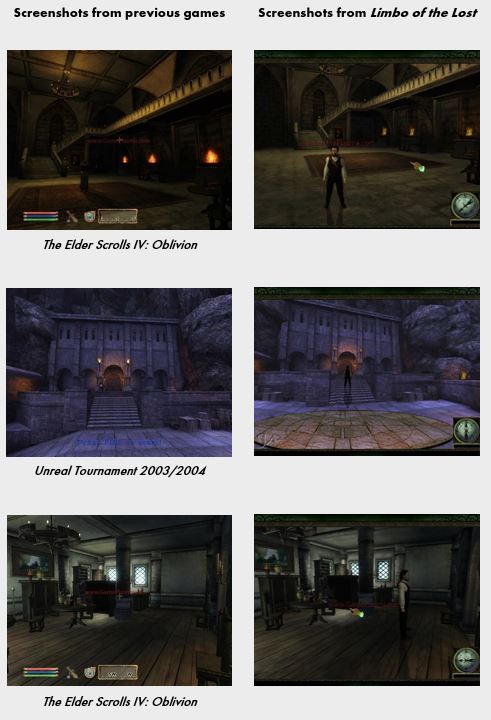

An example is Limbo of the Lost, a game that was eventually withdrawn from sale. Shortly after its release, the online forums were overflowing with posts pointing out graphics and other elements taken from other video games and films. A detailed comparison of individual scenes of Limbo of the Lost with other productions can be found here.

If not copyright law, then what?

-

Protection of a registered industrial design

Due to difficulties in obtaining effective protection against cloning under copyright law, the industry has come up with the idea of protecting elements of a video game (known as “screen display”) by registering it as an industrial design. Since 1992, the US Patent Office has registered more than 14,500 design patents in the category of computer-generated icons. Game elements are also registered as designs at the European Union Intellectual Property Office. We wrote more about this topic in the article on protection of games based on industrial designs, patents and trade secrets.

But protection based on industrial design registration does not seem to guarantee success in the fight against cloning either. First, only certain graphic elements of a game (icons, characters, graphic elements of specific scenes) can be registered as an industrial design, not the whole game. Second, for a design to be valid, it must meet the prerequisites of novelty and individual character. Therefore, it may happen that when the original creator of the game asserts rights to a design, the infringer will present a similar earlier design, which will result in invalidation of the registration. In the case of registration of an industrial design, the method of filing the application, the selection of scenes or fragments to be reserved, as well as the choice of the state of protection, are also very important.

But while design registration does not provide full protection against cloning, it can act as a deterrent to potential infringers, because it shows that the owner of the game is aware of its rights and will enforce them in the event of a dispute.

-

Protection based on the Unfair Competition Act

Notwithstanding the shortcomings of copyright or industrial design protection, the creators of original games do not have to idly watch other developers exploit the fruits of their work.

In Poland, an independent basis for pursuing infringement may be claims provided for in the Unfair Competition Act of 16 April 1993. The act recognises several forms of unfair competition, such as misleading advertising, spreading false information about a competitor or its product, or slavishly imitating the appearance of a product. At the same time, given the difficulty in compiling an exhaustive list of unfair behaviours that may be undertaken by competitors, the act defines an act of unfair competition as “an act contrary to law or fair practice, threatening or infringing the interests of another undertaking or a customer.” One such act of unfair competition is parasitism, i.e. exploiting a competitor’s achievements and market position for one’s own benefit without incurring one’s own financial outlays for this purpose.

It seems that in the case of a clone that has taken over many elements of the original game appreciated by players, resembling the game while maintaining a slightly different expression, an allegation of parasitism may prove valid. This is because a cloner saves on the expenditure for creating a marketable game idea. However, the validity and effectiveness of such an allegation will be determined by the specific facts.

In disputes over game cloning resolved in the United States, a similar allegation is an infringement of “trade dress.” This term covers a set of characteristics of the appearance of a product or its packaging indicating the source of the product to consumers. This protection is intended to prevent consumers from mistakenly purchasing a product that resembles a competitor’s product. This concept has been used in video game disputes, for example, in the case of Tetris Holding, LLC v Xio Interactive, Inc. (US District Court for New Jersey, 2012), regarding alleged cloning of the Tetris game. The court there found that both copyright and trade dress had been infringed.

Territory and the fight against clones

Finally, it should be noted that intellectual property law is governed by the principle of territoriality. This means that if an industrial design has been registered in the Polish Patent Office, the rightholder will be able to prohibit infringement of its rights in the territory of Poland under Polish law. If a design is registered in more than one jurisdiction, the protection against infringement is stronger. Therefore, when deciding to register designs, it is important to consider in which countries the registered design is most likely to be copied or in which markets a given type of game is most popular.

The same will apply when invoking protection under the Unfair Competition Act. This act is intended to protect the Polish market against unauthorised activities. This does not mean that an unfair competition claim cannot be asserted in other countries. However, the entitlement to raise this objection and the specific claims that may be made will be determined, as a rule, by the legislation of the country where the effects of the infringement occurred.

As far as copyright law is concerned, the protection it confers is more widespread, due to numerous international treaties, but it is much more complicated to determine the law applicable to enforcement. As a rule, however, to determine the scope of such protection, the wording of the provisions of the copyright law in force in the country where the rightholder asserts its rights will be decisive. For example, if a Polish company holds the proprietary copyright to a video game, and a clone of its game is distributed in the UK and the infringer is also based there, UK law will apply if the Polish company decides to sue the infringer in the UK.

Ewa Nagy, attorney-at-law, Intellectual Property practice, Wardyński & Partners