The ESPD and grounds for exclusion from public procurement

For many years, contractors have been required to submit a European Single Procurement Document (ESPD) during the course of procedures for award of public contracts in Poland. But the way this form should be completed still raises doubts among contractors and contracting authorities. An example is the question about incidents of early termination of previous contracts. Contractors aren’t sure whether their response to this question should indicate only situations meeting the conditions for exclusion set forth in Art. 109(1)(7) of the Public Procurement Law.

What is the ESPD?

The European Single Procurement Document (ESPD) is a self-declaration by contractors, offered as preliminary evidence. It takes the place of certificates issued by public authorities or third parties. It was introduced by the European Union to deformalise procurement proceedings and facilitate filings by contractors from different member states.

The ESPD is used to confirm that the contractor:

- Is not subject to exclusion from the procedure

- Meets the conditions for participation in the procedure, and

- Fulfils the criteria for evaluation of offers.

The ESPD is intended to give the contracting authority a precise and accurate picture of the situation of each economic operator filing a bid. It thus enables the contracting authority to satisfy itself that each of the tenderers has integrity and is reliable, and, consequently, that the relationship of trust with the economic operator will not be broken. (C-631/21, Taxi Horn Tours BV)

Doubts in interpretation—example

Doubts may arise when filling in the ESPD form on how to properly respond to particular questions. These issues may involve for example questions on the grounds for exclusion of contractors, as in the following question:

|

|

If yes, please provide details: If yes, has the economic operator taken self-cleaning measures? If it has, please describe the measures taken…. |

|

The problem with this question is that there may be doubts whether the response should reflect only the grounds for exclusion (Public Procurement Law Art. 109(1)(7)), or the question has a broader scope than the wording of that provision.

|

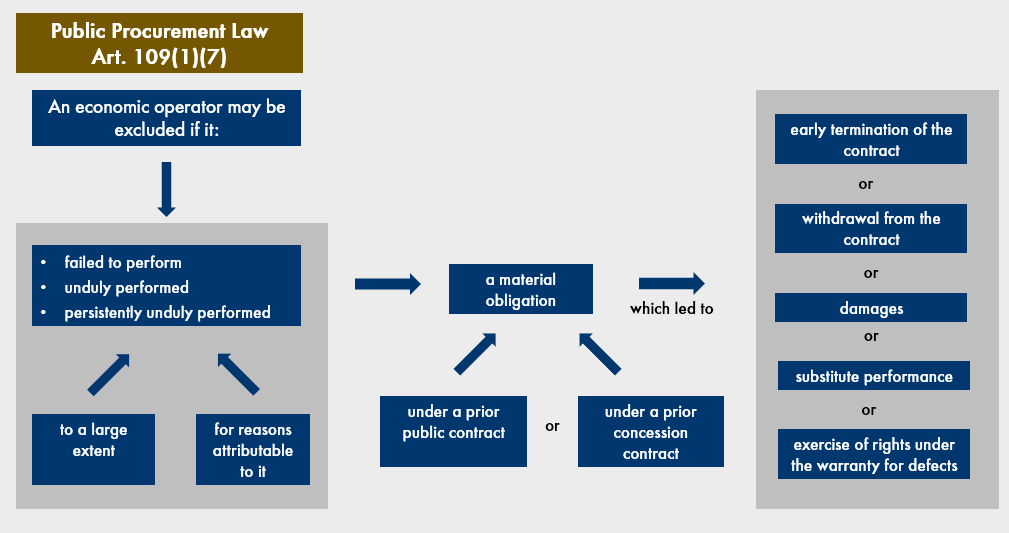

|

The contracting authority may exclude an economic operator from a procurement procedure where the economic operator, for reasons attributable to it, has to a large extent failed to perform or has persistently unduly performed a material obligation under a prior public contract or concession contract, which led to early termination or withdrawal from the prior contract, compensation, substitute performance, or exercise of rights under the warranty for defects. |

|

It is apparent that the wording of this provision does not coincide exactly with the wording of the question in the ESPD form. But it is also clear that the scope of the ESPD question does cover the circumstances indicated in Art. 109(1)(7) of the act.

The Polish Public Procurement Office has issued instructions for completing the ESPD in which it indicates that in response to the foregoing question, the contractor should submit a statement concerning the irregularities in its performance of a prior public procurement contract or concession contract, under the circumstances referred to in Art. 109(1)(7).

But these instructions are not a source of law, and are only intended to help in completing the ESPD. (National Appeal Chamber ruling, case no. KIO 1470/18)

Two different positions

There are two views on whether this question on the ESPD form is strictly correlated with the ground of exclusion set forth in Public Procurement Law Art. 109(1)(7).

Under the first view, this question correlates to the ground for exclusion under Art. 109(1)(7), because the ESPD is intended among other things to confirm the absence of grounds for exclusion. As the ground for exclusion having to do with the circumstances indicated in the question is the one set forth in Art. 109(1)(7) of the act, the contractor does not need to mention any situations that do not meet this ground of exclusion.

As the National Appeal Chamber pointed out in one of its rulings (case no. KIO 3293/2023), the ESPD is not designed to present the economic operator’s entire contract history. The form should include only information about irregularities in performance of previous contract that could lead to exclusion from the contract award procedure.

This interpretation derives from the notion that the ESPD was introduced, among other reasons, to deformalise the procedure. The member states have implemented the “classic” procurement directive (Directive 2014/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 26 February 2014 on public procurement) into their national legal systems, but the final wording of the national regulations is determined by each country’s lawmakers. Differences may crop up in the wording of the grounds for exclusion. Thus the ESPD must contain the broadest possible questions, so that it can be used in any member state without modifying the wording. For this reason as well, the question discussed above in the ESPD form is broad, but its interpretation can be based only on Art. 109(1)(7) of the Public Procurement Law. Consequently, economic operators should state in response to this question only circumstances meeting the grounds set forth in that provision.

Under the second view, in response to this question in the ESPD form, the economic operator must provide information on all circumstances relating to early termination of a contract or having to pay damages or comparable sanctions, even if in the contractor’s own view they do not fulfil the grounds set forth in Art. 109(1)(7). This is because only the contracting authority has a right to verify whether the circumstance in question meets the conditions in that provision. The contractor has no right to determine for itself whether the situation in which it was found suffices to exclude it from the procedure. As the courts and the National Appeal Chamber have repeated, “A contractor cannot be the judge in his own case.”

The question in the ESPD form is unambiguous, as it concerns objective events and enables the contracting authority to check whether the problems encountered by the contractor in the course of performing another project are serious enough and impact enough on the contractor’s reputation that they warrant exclusion from the procedure under Art. 109(1)(7) of the act. This verification is thwarted if the contractor does not provide this information in the ESPD.

Moreover, this manner of interpreting the question and the scope of the necessary response helps maintain another principle of public procurement: transparency. Providing the necessary information in the ESPD enables verification of the information not only by the contracting authority, but also by other contractors, for example via challenges before the National Appeal Chamber. This scope of oversight of selection of the contractor increases the chances that the bidder winning the contract in the procedure will actually ensure proper performance of the contract.

Opponents of this view argue that the question in the ESPD concerns only the ground set forth in Art. 109(1)(7), because it is only on this basis that a contractor can be excluded from the procedure. Thus there is no reason for the response to cover any other circumstances.

It should be pointed out, however, that the cited question in the ESPD form actually has several parts, as there are follow-up questions involving the details of such incidents and potential “self-cleaning” measures (i.e. steps taken by the contractor to eliminate problems that could cause it to be excluded from seeking public contracts). So the question of whether the contractor is subject to exclusion is really found in the next part, asking “has the economic operator taken self-cleaning measures?” If the answer to that question is “yes,” this means that in the contractor’s opinion, there are grounds for exclusion and the contractor had to undergo self-cleaning.

But the contractor could equally answer “no” to that question, in which case the contractor acknowledges that despite the circumstances which it has described in the preceding part of the question, in its view there are insufficient grounds for excluding it from the procedure.

The final assessment is always made by the contracting authority. However, this way of answering the question allows the contractor to:

- Provide an exhaustive description of the overall event, in turn enabling the contracting authority to make its own decision in this respect, and

- Take a stance on the event along with arguments for why, in its view, the event does not warrant excluding the contractor from the procedure.

This means that answering “yes” to the question raised at the outset does not result in an automatic finding that the contractor is subject to exclusion. Thus there is nothing preventing a contractor which believes it is not subject to exclusion from answering “yes” to the question and then, by not underdoing “self-cleaning,” to demonstrate that there are no actual grounds for excluding the contractor.

Conclusion

When weighing the rationale for each of these views, it is essential to have in view not only the good of the contractors, but also the manner in which public monies are disbursed by contracting authorities. The contract should be awarded to a contractor who can ensure that it will complete the contract with due care. For this reason, verification by the contracting authority should rely on a comprehensive analysis of the contractor’s situation.

This is precisely what the ESPD is intended for. The questions included in the ESPD should be interpreted consistent with this purpose. The undisputed link between the two views is that no question in the ESPD establishes new grounds for exclusion. A contractor is always required to demonstrate the grounds set forth in Public Procurement Law Art. 109(1)(7). The response to this question in the ESPD form is only intended to facilitate the contracting authority’s own verification of whether the circumstance in question fulfils the grounds for exclusion set forth in the act. This is what the second of these views achieves.

Rafał Świerzbiński, attorney-at-law, Infrastructure, Transport, Public Procurement & PPP practice, Wardyński & Partners