Payment under a warranty agreement—an alternative to a contractual penalty

In commercial practice in Poland, including M&A transactions, e.g. in share transfer agreements and shareholders’ agreements, the parties often secure their interests with clauses providing for contractual penalties which one party can claim if the other party breaches an obligation under the agreement. Contractual penalties are specifically regulated by the Civil Code. But increasingly, parties protect their interests with the alternative construction of a warranty agreement, which is not specifically regulated by the Civil Code.

Sometimes called a “warranty penalty,” payment under a warranty agreement is an increasingly common mechanism for securing the interests of the parties to business transactions, used in agreements but also increasingly examined in the legal literature and ruled on by the courts. In many respects, payment under a warranty agreement may better protect the interests of a party than the typical structure in Poland of a contractual penalty (also referred to as liquidated damages), which is specifically regulated by the Civil Code.

The essence of the construction

The legal characteristics of payments under a warranty agreement are derived from commercial practice, legal commentaries, and court decisions (for example Supreme Court of Poland judgments of 16 January 2013, case no. II CSK 331/12, and 14 October 2016, case no. I CSK 618/15; Warsaw Court of Appeal judgment of 15 April 2014, case no. I ACa 1435/13; and the most recent case, Supreme Court order of 19 December 2020, case no. V CSK 295/20).

These decisions on warranty payments are drawn from the broader area of warranty agreements, which according to the legal literature (see J. Jastrzębski, “Non-insurance warranty agreements,” PPH 2018 no. 7) includes:

- Agreements creating the warrantor’s obligation to pay under a warranty, intended to satisfy indirectly an interest of the beneficiary that cannot be directly satisfied by the warrantor’s behaviour, which could be traditionally understood as performance by the obligor (for example, a contractual obligation on the part of the warrantor to act in good faith for the purpose of obtaining a third-party permit or administrative decision necessary for completion of the transfer of shares to the buyer), or

- If the parties’ intent is not to create a performance obligation directly satisfying the beneficiary, but only to indirectly secure it with a warranty payment (i.e. the parties’ intent is only to economically protect the beneficiary from the negative consequences of failure to achieve the result originally intended by the parties).

This article discusses only the second of these types of warranty agreements, i.e. involving an obligation by one party (the warrantor) to make a payment to the other party (the beneficiary) if certain circumstances arise, which constitute the warranty risk.

In the most general terms, in this sense clauses providing for payment under a warranty agreement, which can be an alternative to a contractual penalty, consist in imposing an obligation to pay a sum of money (defined as a specific amount or calculated under a formula provided for in the agreement) in the event of materialisation of the warranty risk, which, as it seems, may be breach of an obligation due to circumstances for which the obligor (the party to the agreement that should fulfil the obligation, which might be the warrantor itself) is not responsible. The provisions of the Civil Code on contractual penalties do not apply to payment under a warranty agreement in this sense. Thus this is a separate liability regime, different from the basic (statutory) liability regime for the consequences of breach of obligations under the Civil Code, in particular Art. 471 (contractual liability) and Art. 472 (debtor’s liability).

The key features of the construction of payment under a warranty include the following:

- The construction does not derive from the code, but must be expressly introduced by the parties through a contractual clause

- The construction is based on the principle of freedom of contract under Civil Code Art. 3531

- The obligation to pay under the warranty arises regardless of whether the beneficiary has suffered any loss as a result of materialisation of the warranty risk, including breach of a contractual obligation by the other party (which may be the warrantor itself)

- The obligation to pay under the warranty occurs independently of whether the party to the agreement (which may be the warrantor itself) that breached its contractual obligation (if this constitutes the warranty risk) is liable for breach of its obligation (i.e. objective liability)

- The amount of the payment under the warranty indicated in the agreement, or resulting from proper calculation under the formula stated in the warranty agreement, is not subject to mitigation (reduction) by the court.

These features demonstrate that payment under a warranty, and thus the contractual liability regime constructed on this basis, is framed differently from the general rules of contractual liability under the Civil Code.

The primary reason for use of the warranty structure is that M&A agreements (share transfer agreements or shareholders’ agreements) are generally based on constructions from common-law jurisdictions, and like their prototypes should be comprehensive, excluding wherever possible application of default provisions of the Civil Code. In essence, payment under a warranty serves as a special contractual liability construction agreed by the parties, who are typically professionals in this area.

Payment under a warranty agreement vs. contractual penalties

Perhaps the most important difference between a warranty payment and a contractual penalty is that the obligation to pay under a warranty is primary, i.e. in the legal sense, in principle, the warrantor’s payment is not intended to protect the beneficiary from materialisation of the warranty risk and compensate for the resulting injury; rather, the warranty payment (as a result of materialisation of the warranty risk) is intended to compensate the beneficiary economically for the state of affairs resulting from the mere materialisation of the risk. By contrast, a contractual penalty is designed to compensate for injury arising from breach of a non-monetary obligation. In this understanding of the structure of contractual penalties, the obligor’s primary obligation is to perform under the contract, and only in the event of non-performance or improper performance does the derivative obligation to pay a contractual penalty arise. And in the mechanism of a contractual penalty, that the claimant has suffered injury, and the amount of the injury, are both relevant, while under warranty liability the existence of injury has no legal significance.

Another difference, no less important, is the impact of the obligor’s conduct in fulfilling the secured obligation and the types of circumstances in which breach of the obligation results in the obligor’s liability. A contractual penalty is due only if breach is a result of circumstances for which that obligor is responsible. Thus a contractual penalty is not due when breach of the obligation is a result of circumstances for which the debtor is not responsible (although this rule can be modified contractually). However, even making the appropriate contractual modification of the statutory rules, the obligor’s primary obligation is always to perform under the contract, and payment of a contractual penalty is a secondary, derivative obligation. In contrast, in the case of payment under a warranty, the obligor’s possible contribution (i.e. fault) to materialisation of the warranty risk, including breach of the obligation (if this is the warranty risk), or the types of circumstances causing the warranty risk to materialise, do not affect the obligation to pay under the warranty agreement as a result of materialisation of the risk. Thus, the obligation to pay under a warranty agreement as a result of materialisation of the warranty risk is detached from the circumstances causing the risk to materialise, and the warrantor cannot avoid paying by invoking such circumstances.

Another important difference is the statutory possibility (Civil Code Art. 484 §2) of mitigating the stipulated amount of the contractual penalty, at the request of the obligor:

- If the obligor performed in substantial part, or

- When the contractual penalty is grossly excessive.

But in the structure of payment under a warranty agreement, the warrantor cannot challenge the contractually stipulated amount of the payment, as held by the Supreme Court in its order of 19 December 2020 (case no. V CSK 295/20): “Inclusion in an agreement of a reservation of a warranty nature, imposing an obligation to pay a certain amount of money in the event of non-performance (or improper performance) of an obligation due to circumstances for which the obligor is not responsible, not governed by the provisions on contractual penalties, is permissible (Supreme Court judgment of 16 January 2013, case no. II CSK 331/12, Lex no. 1293724). Since by definition this is a different type of contractual reservation than a contractual penalty under the code, no grounds exist for applying Civil Code Art. 484 by analogy.”

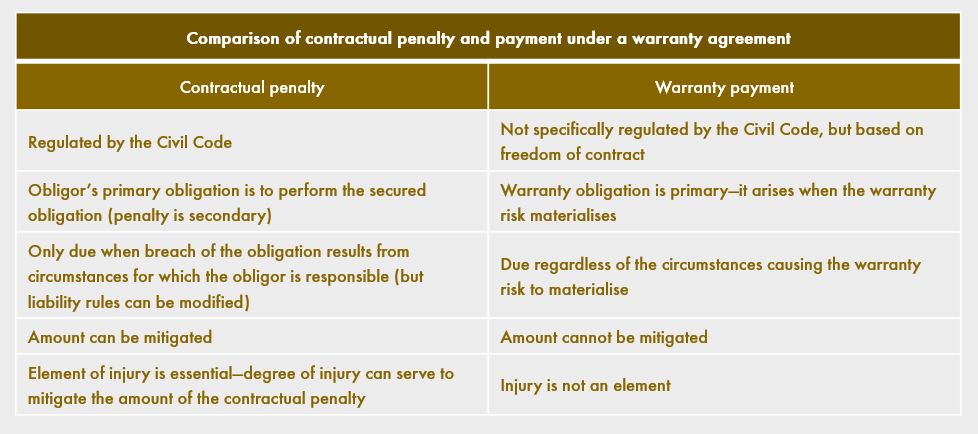

The differences can be summarised as follows:

Advantageous for the beneficiary

As a mechanism to secure the beneficiary’s interest, payment under a warranty agreement offers a more favourable construction than a contractual penalty, for the following reasons:

- The obligation to pay under the warranty agreement is detached from the occurrence of damage or the extent of damage on the part of the beneficiary resulting from materialisation of the warranty risk

- The obligation to pay under a warranty agreement is detached from the type of circumstances giving rise to materialisation of the warranty risk and the possible contribution of the obligor (which may be the warrantor itself) to materialisation of the warranty risk

- The amount of the payment under a warranty agreement stipulated in the agreement may not be mitigated at the warrantor’s request.

Most often, in current M&A transactions, the construction of payment under a warranty agreement is used specifically to secure the performance of:

- Obligations under a drag-along right (such as conclusion of the share transfer agreement at the proper time and place, and taking other steps by the obligor)

- Obligations during the interim period

- Obligations arising from non-compete clauses

- Obligations with respect to protecting confidential information

- Other obligations under the transaction documentation.

Legal basis for the construction

The construction of payment under the warranty agreement is not specifically regulated in the Civil Code. This mechanism is backed by the principle of freedom of contract expressed in Civil Code Art. 3531, as confirmed in the cases from the Supreme Court cited earlier. Despite the similar features of contractual penalties and payment under a warranty agreement, the provisions of the Civil Code regarding contractual penalties, including the possibility of reducing the amount reserved by the parties, should not be applied to payment under a warranty agreement due to the significant differences between the two structures.

But in this regard it is possible that the decisions of the state courts may change over time. For example, the courts might regard contractual clauses requiring payment under a warranty agreement as an attempt to circumvent the provisions on contractual penalties. For this reason, it may be appropriate to include arbitration clauses in agreements providing for payment under warranty agreements. And it should always be noted that payment under a warranty agreement should not be used as a structure to circumvent the statutory ban on imposing contractual penalties for non-performance of monetary obligations.

For these reasons, it is essential to thoroughly analyse the contractual obligations to be secured by payment under a warranty agreement, so that the contractual clauses adopted by the parties are upheld as fully valid and effective in light of the existing case law and legal literature (which, it should be stressed, is still taking shape).

Note that the author takes the view (contrary to some current commentators) that it is sufficient to identify the mere breach of another obligation as the warranty risk.

Krzysztof Drzymała, M&A and Corporate practice, Wardyński & Partners